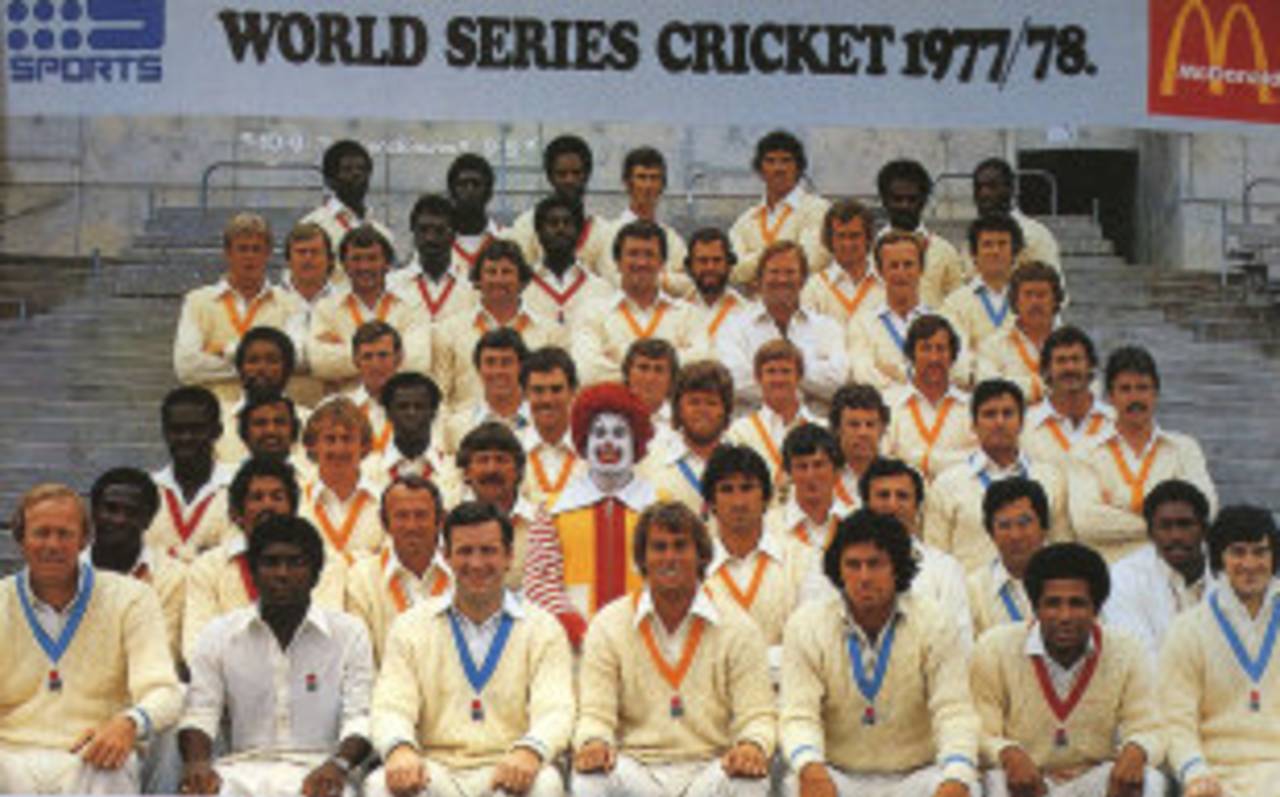

World Series Cricket was more seismic, seditious and schismatic than any other event in the history of the game, including Bodyline. It was born in 1977, effectively the upshot of conflicting standpoints best summed up by Kerry Packer, the ringmaster himself, and John Woodcock, the esteemed correspondent of the Times. These came not just from different sides of the world and sport itself but seemingly from different eras.

To Packer, the brash, hammer-headed shark (in all senses), who initially was after broadcasting rights from the ACB, it was: "Come on, now, we're all harlots - what's your price?" For Woodcock, who had begun his career at a time when many of the best players were not paid anything at all, there was an incomprehension that their successors would turn out in this irreverent showbiz enterprise and hence put their Test careers at risk. "I did not appreciate," he said reflectively years later, "that every man has his price."

And the game of cricket paid the price. Much of its decorum, beloved by Woodcock's generation, disappeared in the face of innovation after innovation. "Helmet Heresy," thundered the Cricketer on its cover, although in truth the health and safety brigade would have been on the scene not that long after Packer. Weaving and ducking and bouncers and intimidation were all encouraged, although there had been plenty of that from the Australian and West Indian fast bowlers in the mid-1970s. When David Hookes' jaw was broken by Andy Roberts in Sydney in 1977, protective headgear became a necessity.

There appeared to be little room in this brutalised form of the game for the craftsman, the grafter, even the spinner, as the action revolved around short-pitched bowling with white balls, big hitting, catchy tunes - "C'mon, Aussie, c'mon…" - on drop-in pitches, under floodlights, in coloured clothing, within restrictive fielding circles, and horror of horrors, on football grounds. Football and cricket were now inter-changeable entertainments.

Floodlit cricket was Packer's idea - and for that, the game, or at least the bean counters, should be grateful. Several decades on, the ECB even provides funds to county clubs to hoist their own pylons in the most traditional of settings to offset horrendous annual loses. Packer himself had helped man the turnstiles and eventually threw them open when it was apparent at the first night match, in Sydney, that this was going to be a triumph. According to the ground authorities 52,000 spectators tried to get in that evening, and actually did so.

Another of Packer's masterstrokes was to appoint Richie Benaud, the most knowledgeable and - it was assumed - traditional of cricketing men, to promote his form of the game. "It was fun," Benaud said and would still say, while chronicling the benefits to the game. The most significant of these, he believes (as, of course, Tony Greig was constantly propounding) was that the most average players, as well as the very best, would now be properly paid. Benaud believed night cricket was one of the most exciting spectacles he had ever seen.

The success of these innovations can best be gauged by the fact that most of them are now an accepted part of the game. Of course the coloured clothing is garish. Of course there is too much one-day cricket. Of course it is too packaged and too artificial. But Packer knew his market and, several years after his death, this is still popular with the public. At this distance of time, what appears most bizarre is that the administrators, the "establishment" for want of a better description, never saw any of this coming. Shortly after the news broke, EW Swanton wrote of "the deception of men who are making a handsome living out of the game" and that "out of evil good may come". The truth of the matter was that he had been better remunerated by the Daily Telegraph than England players, who were earning £180 per Test.

Swanton and his ilk must have realised - surely some of them must have done - that not every Test cricketer would want to continue to play for little remuneration. The maximum wage had been lifted in football, the age of the amateur cricketer was over, and anyway the very best of those players, Peter May and Ted Dexter, had retired prematurely because, in the latter's words, "the bills had to be paid". There was little foresight, however honourable the intention to preserve the game in its purest form.

That played straight into Packer's hands. The upshot was the gaudy, irreversible commercialisation of cricket, much of which survives to this day.

This article is the second of a ten-part series on innovations in cricket, in partnership with Saab. Next week, the birth of limited-overs cricket